Intangible assets: developing a tax strategy

Intangible assets: developing a tax strategy

Intangible assets – the context

Businesses continue to have focus on investment in innovation and, with it, a raft of new intangible assets.

At any point in time, emerging technologies are creating value in new ways and disrupting existing markets. Across every sector, there are new market entrants with innovative operating models and value propositions, including the automation of historically manual processes. Coupled with this, there is constant evolution in the form of changing consumer demands and shifting consumer markets, and a need for companies to adapt alongside. Businesses are either disrupting or being disrupted, and both demand investment in intangible assets.

It is clear for some businesses that value creation is predominantly driven by intangible assets. Across the board, the role of intangibles in value creation for groups is significant and will increase over time. Intangibles are not just important for service and 'tech' businesses. A study by the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO), WIPO Report 2017: Intangible capital in global value chains, concludes that on average, from sectors as diverse as motor manufacture through to food and beverages, intangible assets constitute a third of the value of the product purchased by consumers. More recent commentary (e.g. analysis of the S&P 500) suggests that proportion is increasing.

Intangible assets are not just important in a commercial context. There has also been increasing focus from an international tax perspective on how, and where, intangible asset derived profits should be taxed.

The OECD BEPS initiative produced 15 action reports in 2015 for rebooting the international tax system, many of which cover the taxation of intangible assets. This is seen in the discussion and proposals in respect of hybrid mismatches in Action 2, where a key focus has been on stateless income associated with intangible assets. The Action 5 papers demonstrate a desire to ensure that jurisdictions seek to attract IP rich companies in ways that are properly reflective of the business activities. The report on Actions 8–10 focuses on the alignment of people, substance and profit for the most mobile asset classes, such as intangible assets.

In more recent times, we have seen continued focus on ensuring effective taxation of intangible assets with measures tackling base erosion from the “offshoring” of IP in a number of territories, and a continuing perception that multinational companies can manipulate the tax they pay through mobile assets such as intangible assets, which was a key driver in the OECD Pillar 2 initiative. We have also seen focus on disclosure obligations for certain intragroup transactions, including intangible asset restructuring, as well as establishing a new framework around “hard to value intangibles” (HTVI) within the OECD guidelines which enable tax authorities to consider ex post outcomes as presumptive evidence as to the reasonableness of the projects used on an ex ante basis in determining the pricing of a transaction involving intangibles between associated enterprises..

The existence of tax incentive regimes for intangible assets and development activity is now a feature in many tax jurisdictions, and competition will continue for innovation and investment. The form of that competition will vary as a result of global initiatives such as the OECD Pillar 2 initiative. However, as long as intangibles continue to drive substantial value within multinational companies, competition will remain, and likewise, associated controversy.

Given the importance of intangibles for businesses and the changing tax environment, it is critical that groups take steps to establish an intangible asset strategy. As well as opportunity in action being proactively taken, there is risk in action not being taken — both opportunity cost, but also where the substance of a business's value creation has evolved away from the legal form of its intangible asset structure.

If you would like to discuss the tax impact of your intangible asset strategy, please contact Ross Robertson.

An approach to developing an intangible asset strategy

In this document, intangible assets strategy refers to the considered approach of a business to the development, protection and exploitation of its intangible assets. The development of an intangible asset strategy requires careful thought. Whilst there can be no 'one size fits all' process, we have set out an approach for defining an intangible assets tax strategy that can be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Step 1: Intangible asset identification

As a first step, it is important to comprehensively identify the intangible assets of a business.

This means identifying what assets the business has, who owns those assets (legally and, if different, beneficially and economically) and then mapping that understanding onto tax and transfer pricing definitions of intellectual property and intangible assets.

Identification of intangible assets needs to go far deeper than registered intellectual property rights (such as registered trademarks, patents, etc.). This is a common failing in the scoping of an intangible assets strategy, and it leads groups to not think broadly enough about the intangible assets within their organisation. The consequence is that it is then challenging to accurately articulate how the business really drives value from these assets (and to then optimise that and manage associated risks).

Beyond the registered intellectual property rights, the intangible assets strategy needs to consider unregistered intellectual property rights (such as unregistered trademarks, copyright, design rights and data rights), as well as other intangible property (such as goodwill, know how, trade secrets and confidential information).

Having identified the assets of the business, it is necessary to reflect on the ownership of those assets — legally and 'economically'.

Legal ownership of intangible property is itself a complex area. There are circumstances in which intellectual property rights arise to whoever registers them; and there are circumstances in which the rights may arise to the inventor directly or to the employing company of the inventor. The law differs around the world, and for different types of asset.

In terms of 'economic' ownership, for transfer pricing purposes it is the people functions relating to the intangible assets that attract the profits (see below). Economic ownership will inform the approach to transition to a new intangible assets strategy and may define the ability to access certain incentive regimes. In some cases, legal ownership may be split from economic ownership, such as where the rights to a patent are transferred but the legal transfer itself is not perfected, and again that is important to capture to better inform later thinking. There are also considerations around 'beneficial ownership' that are important for tax treaty application (e.g. on withholding tax, or accessing the benefits of a treaty on an income flow).

In domestic tax law terms, the definition of intellectual property and intangible assets varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, but many tax definitions build from an accounting framework (such as in the UK). Therefore, it is often necessary to take the legal context and apply accounting concepts to identify intangible assets that are capable of recognition separate from the goodwill of an enterprise, and those that may be more likely to form part of the goodwill of an enterprise.

By contrast, the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines define an intangible asset as something which is not a physical or financial asset, which is capable of being owned or controlled for use in commercial activities, and whose use or transfer would be compensated had it occurred in a transaction between independent parties in comparable circumstances. This is a very broad definition and may be broader than the tax definition. It is certainly broader than the legal definition of intellectual property.

Understanding the intangible assets of a business, and how that maps against the relevant definitions for tax and transfer pricing purposes in the jurisdictions in which the business operates, will be a key building block of the intangible assets strategy.

Step 2: Assessment of the value chain and role of intangibles

Having identified the intangible assets of the business, it is necessary to review the value chain to establish the importance of these assets. The concept of the value chain references how (and where) a business creates value and is the critical context for valuation assessment.

The value chain is the anchor for the creation of transfer pricing policies. Furthermore, the value chain, and principal contributions to value creation, need to be disclosed in the new 'masterfile' standard introduced in the course of the OECD BEPS initiative (as do important intangibles).

Mapping the value chain also necessitates the identification of 'substance' within the business operations. Substance can be broadly interpreted as the alignment of transfer pricing outcomes with value creation. The role of people is of paramount importance.

That alignment is effected through accurately delineating a transaction with reference to the activities and controls of people functions, ownership of assets and assumption of risk, in light of the contractual (legal) position. Substance is articulated through a functional analysis, and will also form part of the master and local files.

When defining a tax strategy, there are three critical transfer pricing concepts to consider.

A. Control of the DEMPE functions

The first concept is that bare legal title to intangible assets yields minimal entitlement to any intangible related return. In other words, mere legal ownership of an intangible asset by a company does not mean that the company should be entitled to any meaningful return for transfer pricing purposes.

Rather, understanding the location of functions relating to the development, enhancement, maintenance, protection and exploitation ('DEMPE' functions) of the intangible asset is critical. In fact, it is control of the DEMPE functions that is most important to the assessment of entitlement to intangibles related returns. Execution functions are not likely to generate material entitlement to profit. It is the development, setting and control of the strategy (and bearing the risk consequences) that is likely to earn residual profit associated with the exploitation of intangible assets once 'routine' functions within the business have been rewarded.

B. A 'two-sided' approach

The related second concept is that a 'two sided' approach to transfer pricing is increasingly required. It is no longer sufficient to price the return for the least complex party and pay away the residual to the owner of the intangible assets. Rather, entitlement to intangible related returns should be defined by reference to functions actually carried on by an intangible asset owning entity (and assets employed/risks assumed), not by an assumption that it must carry on those functions as they are not carried on in the counter party.

C. Business restructuring transfer pricing

The third concept is that a transfer of legal title and/or DEMPE functions within a group will require assessment under transfer pricing business restructuring provisions (the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines Chapter IX), in light of the 'options realistically available' to the transferor. In other words, would the transferor have agreed to the restructuring on the proposed terms with an independent third party?

Compensation may be due to the transferor by reference to what would have happened with regard to its next best option. This is, importantly, not the same as saying that performance of the DEMPE functions give rise to 'ownership' of the intangible assets themselves. Entitlement to capital returns on disposal of intangible assets is a complex area that is beyond the scope of this article. Suffice to say for now that movement of both DEMPE functions and legal ownership of intangible assets require careful consideration.

Putting these concepts together, it will be critical to understand who in the organisation is driving value in respect of each of the intangible assets and where they are driving that value from, and ensure that the business is able to react to the implications if the business undergoes a restructuring of its operations (either in terms of roles or geographies).

Step 3: Commercial objectives and business plans

An intangible assets tax strategy needs to take account of the current business environment, and be adaptable.

To achieve this, it is necessary to identify and factor in planned change, and consider the potential impact of further changes that may occur. Partly, this will be about managing the impact of known change; partly about building in flexibility for the unexpected.

In both cases, this will require businesses to balance business operations with governance. The intangible assets strategy should be capable of delivering robust, predictable tax outcomes, but governance needs to not be overly restrictive as this could discourage the business from being entrepreneurial and opportunistic.

An intangible assets strategy affects a wide range of stakeholders across a business, from business operations, IT, HR and legal, as well as tax (to name a few). All of these stakeholders need to be identified and brought together to determine the right strategy for the group.

The tax function of a group cannot act in a silo in defining an intangible assets tax strategy. In a post BEPS environment, tax outcomes can only be achieved if the business 'lives' the tax model. Therefore, the focus for the tax team needs to be on optimising business operations, avoiding restrictive governance and minimising business disruption. In other words, it needs to be business led.

Step 4: Assessment and application of Incentive regimes

There may be tax incentives for intangibles related returns accruing in certain territories. This often arises through the application of incentive regimes designed to stimulate the development or exploitation of intangibles in a particular market. These regimes typically focus on the narrower band of registered intellectual property rights of a business, but some regimes (such as the UK patent box regime) may then permit a broader category of intangible derived profits to benefit from the regime, provided threshold criteria in respect of the registered intellectual property rights themselves are met.

As such, tax outcomes are impacted where the business profits arise in a territory with an attractive intellectual property regime. However, the strategy for accessing these incentives must align with real business activities relating to the intangible assets under transfer pricing principles (ie the DEMPE functions must be undertaken in the territory in which the innovation incentive is being claimed). It is also often important that physical R&D activity is led from and/or undertaken within the territory.

If substance and legal form can be aligned to obtain access to an intellectual property incentive regime, then it is worth giving careful thought to the operating model and how that interacts with the parameters of a particular regime.

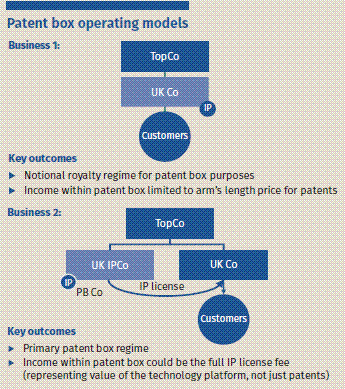

The UK patent box regime is a good example of how the operating model can substantially impact the application of the regime. For the UK patent box regime, an important point to note is that a patent is a criterion of access to the regime, but having passed that threshold, a broader range of profits than those directly attributable to the patent can be brought within the regime. This is most easily explained through an example.

Take a company that uses a technology platform to deliver services to its customers ('Business 1'). Imagine the company owns that technology platform itself, and that a component of that technology platform is patented. The patent box profits would be restricted, broadly, to the amount that the company would pay a third party on arm's length terms for access to the patent.

Now imagine a business operating under a different business model ('Business 2') where in this case a company owns a technology platform and licenses the right of use of the technology platform to a customer facing company to enable the delivery of services. In this model, the full licence income of the platform owning licensor company (and not just the income directly attributable to the patented component) is potentially capable of falling within the patent box regime where all of the platform rights are licensed together for the same purpose (e.g. for the delivery of the services to end customers). The difference between the value of the technology platform in full, and the patented component of a technology platform, can be significant, and therefore the different business models could see a very different application of the patent box rules. Transition in business model may be possible, subject to detailed consideration of the commercial context driving any change and the application of the patent box rules in light of that.

Similar considerations apply for other incentive regimes around the world. Therefore, the operating model and the intangible asset strategy of a group should be considered closely together.

Step 5: Assessing transitional tax consequences

One of the most significant potential financial challenges with the implementation of a new intangible assets tax strategy relates to transition costs to achieve the desired new structure. As intangible assets are valuable assets that are often internally developed (therefore with minimal associated tax base cost), the tax charge triggered on any taxable transfer of intangibles assets can be significant.

A few alternatives to the transition can be considered in this respect:

- Income versus capital transactions; and

- Wither on the vine.

Income versus capital transactions

Take a situation where the intangible assets of a group are owned by a number of group companies overseas, and for commercial and tax reasons there is a desire to align the ownership of these intangible assets with the business substance that is increasingly driving the development and strategy in respect of these assets from the UK (creating an 'intangibles hub').

A 'capital' variant of the transaction would be to effect an outright transfer or assignment of the intangible assets from overseas locations to the UK. This would likely trigger local territory exit considerations, and would be treated as a capital transaction from a UK perspective. This would mean that from a UK perspective, it would be necessary to consider the application of capital allowances or tax amortisation to the acquired intangibles (which can be an important point where, for example, goodwill is acquired). However, withholding tax is unlikely to be in point on the transfer consideration, and likewise 'income based' anti-avoidance provisions, such as the relatively recent hybrid and other mismatch provisions and UK diverted profits tax, are unlikely to apply (though would of course require consideration).

An 'income' variant of the transaction could be to license the intangible asset rights to the UK, and realign the business operations and transfer pricing policy to determine the appropriate amount that may be payable to the licensor under transfer pricing principles and the entitlement of the UK to the residual profit. In this scenario, it may be the case that there is a different exit analysis in historic IP owning overseas territories. Further, we need to consider the deductibility of royalty payments in the UK, rather than the application of capital allowances or amortisation. Provisions relating to withholding tax, hybrid and other mismatch provisions and the diverted profits tax are more likely to be in point.

A 'wither on the vine' approach

A 'wither on the vine' approach refers to a hybrid of the above approaches. Ownership of the existing intangible assets would remain unaffected, but investment in new intangible development activity would be made (in this case) from the UK and ownership of new intangible assets would vest with the UK business. Typically, there would be a licence of the existing intangible assets to the UK, and the UK would exploit the combined pool of 'new' and 'old' intangibles together. The licence fee payable for the legacy intangible assets in overseas territories would decline over time, as they are superseded by intangible assets of the UK company, and gradually become obsolete.

This approach may help to manage risks relating to a local territory exit (detailed analysis of the OECD transfer pricing guidelines on business restructurings would be required); however, the pace of transition to the new model is dependent upon the useful life of the legacy intangible assets. If those assets continue to be of key importance to the group for an extended period, the transition to a wholly UK centric model could take a number of years.

There is no 'right or wrong' approach to transition. Rather, each transition should be viewed on its facts to assess the best approach for the circumstances. And of course, the impact of the application of the OECD Pillar 2 rules for any restructuring should not be overlooked.

Step 6: Monitor and evolve

Nothing stands still from either a commercial perspective or an international tax perspective. Therefore, any implemented strategy will require constant monitoring and regular review to ensure that it continues to align with the substance of the business value generation, and is appropriately managing emergent tax risk.

This should take the form of regular reviews of business operations to ensure any evolution is captured, and tracking the intangible asset pipeline to ensure that the future value drivers of the business are considered in the framework of the strategy as early in the development cycle as possible. It also requires continua monitoring of the global tax environment. Where the business or tax environment evolves, the intangibles assets strategy should be updated accordingly.

Transitional considerations on establishment of a UK intangibles hub

|

|

'Income' variant transition |

'Capital' variant transition |

|

Existing intangibles owner |

||

|

Exit risk |

Business restructuring |

Capital disposal |

|

New intangibles owner |

||

|

Deduction from income |

Royalties |

Capital allowances/amortisation |

|

Withholding tax (acquisition/use of intangibles) |

Requires consideration |

Unlikely to be in point |

|

Anti-hybrid |

Requires consideration |

Unlikely to be in point |

|

Diverted profits tax |

Requires consideration |

Unlikely to be in point |

|

Pillar 2 |

Requires considerations |

Requires consideration |

|

MDR / DAC 6 |

Requires consideration |

Requires consideration |

Conclusion

The development of an intangible assets tax strategy is a multi-faceted discussion and is likely to be one of the more challenging aspects of the overall tax strategy in the current rapidly evolving tax and business environment. However, it is also likely to be one of the most important, due to the increasing importance of intangible assets from a commercial perspective and the increasing focus on their taxation from a tax perspective. An effective strategy can realise significant opportunities. The absence of a strategy can create material risks.

Whilst there is no one size fits all approach, each strategy will proceed through the stages of:

- Intangible asset identification

- Assessment of the value chain

- Consideration of commercial objectives and business plan

- Identification and application of available incentive regimes

- Assessment of transitional strategies, and

- Monitoring and evolving the strategy to ensure it remains business aligned and fit for purpose.

Each well-constructed strategy will likely have similar features:

- The structure will be effective in a fully transparent environment.

- Functions controlling the DEMPE of intangibles are clearly aligned with the locations of the relevant intangibles related returns. The business needs to 'live' the approach that is documented for transfer pricing purposes, otherwise the proposed tax outcomes will not follow.

- It will use statutorily available tax incentives such as capital allowances/tax amortisation/incentive regimes, and low statutory rates for non-qualifying income – but noting the overlay of the OECD Pillar 2 rules

- There will be considerations of treaty networks and substance to support treaty access.

- There will be clear definition of payments for intangible assets (restructuring or ongoing), supported by intra-group agreements.

- There will be consideration of the approach to unwinding or changing the strategy if the business, or the wider environment, changes.

Those who are able to get ahead of their intangible assets tax strategy will likely reap the rewards. Those who look to approach the management of the taxation intangible assets strategy in a reactive way are likely to be exposed to an increasing spectrum of risk, and increased cost.